Quarantine is not a 30-day waiting period; it is an active investigation that operates on the assumption that every new animal is guilty of carrying disease until proven innocent.

- Healthy-looking animals can be “Trojan Horses,” silently shedding viruses like BVD and infecting your entire herd.

- Indirect contact through shared trailers, contaminated boots, or even visitors poses as significant a threat as nose-to-nose contact.

Recommendation: Do not just isolate new animals; build a multi-layered “biosecurity fortress” with strict physical separation, targeted diagnostic testing, and rigorous protocols for all equipment and personnel.

That prize-winning bull from the auction looks perfect. It’s healthy, strong, and shows no sign of illness. Bringing it onto your farm feels like a victory. But in the world of biosecurity, this is the most dangerous moment. A healthy appearance is a mask that can hide a devastating secret. The biggest mistake a producer can make is to trust their eyes. The common advice is to simply “isolate new animals,” but this passive approach is an open invitation to disaster.

The reality is that epizootic diseases don’t announce their arrival. They sneak in, carried by asymptomatic animals that act as biological Trojan Horses. Standard checklists often fail because they don’t address the core problem: a lack of productive paranoia. They focus on what to do, but not on the mindset required to do it effectively. True biosecurity is not a set of tasks; it is a philosophy built on the unshakeable principle of “guilty until proven innocent.” Every new animal, every visitor, every piece of shared equipment is a potential vector for an outbreak.

This guide abandons the naive “wait and see” approach. Instead, it provides a strict, systematic framework for building a biosecurity fortress. We will dissect the hidden dangers of subclinical carriers, design an impenetrable quarantine zone, evaluate aggressive testing strategies, and establish non-negotiable protocols for every potential point of failure—from trailers to visitors. The goal is to shift your perspective from simple isolation to active, paranoid, and effective defense.

To construct this biosecurity fortress, we will explore each layer of defense in detail. The following sections break down the critical components, from understanding the invisible enemy to implementing the daily protocols that ensure your herd remains protected.

Summary: A Systematic Approach to Farm Biosecurity

- Why Healthy-Looking Animals Can Still Carry Viral Diseases?

- How to Set Up a Quarantine Zone Separate from the Main Herd?

- Test-and-Wait or Treat-All: Which Quarantine Strategy is Safer?

- The Trailer Sharing Habit That Transmits Foot-and-Mouth Disease

- How to Manage Visitor Access to Protect High-Health Herds?

- How to Design a Chemical Storage Shed That Meets All Codes?

- Group Housing or Stalls: Which Improves Sow Longevity?

- Why Monthly Veterinary Audits Save Money on Emergency Calls?

Why Healthy-Looking Animals Can Still Carry Viral Diseases?

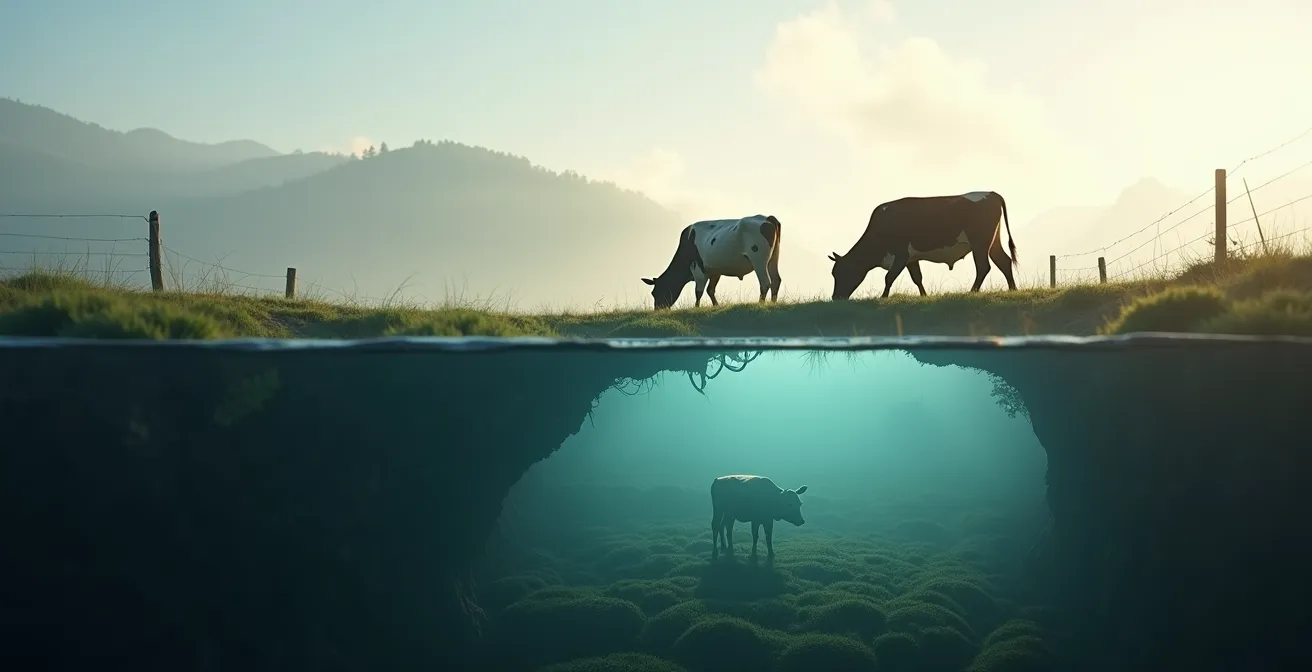

The single most dangerous assumption in livestock management is that a healthy-looking animal is a healthy animal. The truth is that many of the most devastating epizootic diseases are spread by subclinical or asymptomatic carriers. These are the biological Trojan Horses that walk right through your farm gates. This phenomenon is often described as the “iceberg effect”: for every visibly sick animal you see, there could be dozens more in the herd that are infected and actively shedding pathogens without showing any symptoms themselves. They are mobile, silent sources of infection.

A prime example is Bovine Viral Diarrhea (BVD). An animal’s immune system can be compromised, leading to other illnesses, but the real threat comes from Persistently Infected (PI) animals. As Cornell University’s Animal Health Diagnostic Center explains, a cow exposed to BVD during a specific window of pregnancy can give birth to a PI calf. For its entire life, this calf is a “virus factory.” The case study on Persistently Infected Cattle as Disease Reservoirs highlights a critical danger: a PI calf will shed massive amounts of the BVD virus, capable of infecting any other animal it comes into contact with, all while potentially appearing completely normal.

This is why visual inspection is an unreliable and reckless method for clearing new stock. The absence of symptoms is not evidence of health; it is simply a lack of visible evidence. Every new animal must be treated as a potential PI carrier or asymptomatic shedder until proven otherwise through rigorous testing.

How to Set Up a Quarantine Zone Separate from the Main Herd?

A quarantine zone is not just a separate pen; it is a purpose-built biosecurity fortress designed to contain a potential outbreak. Its design and management must assume that the animals within it are infectious. Every detail, from its location to its equipment, must be geared towards preventing any cross-contamination with the main herd. The location itself is the first line of defense. Ideally, the quarantine area should be located as far as practically possible from other livestock areas, taking into account wind direction and water runoff to prevent airborne or waterborne pathogen transmission. A minimum distance of 50 meters is a good starting point if space allows.

The physical barriers must be absolute. Standard fencing is not enough. To prevent any chance of nose-to-nose contact, which is a primary route of transmission, fence lines should be double-stranded or hot-wired. All equipment used in the quarantine zone must be exclusive to that zone. This includes feed and water troughs, handling equipment, and cleaning tools. Using portable troughs is a smart practice, as they can be completely removed, cleaned, and disinfected between batches of new animals, breaking the cycle of contamination. Finally, access control for vehicles and personnel is non-negotiable. Any vehicle entering the quarantine zone must not be allowed into other paddocks without a thorough wash-down. A simple footbath with disinfectant and a hose at the gate are low-cost, high-impact tools to enforce this rule for staff boots and equipment wheels.

The level of risk associated with incoming animals should dictate the strictness of your quarantine protocol. Not all new animals carry the same threat level, and your strategy should reflect that.

| Risk Level | Source Type | Quarantine Duration | Testing Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| High (Level 1) | Unknown/Auction sources | Minimum 30 days | Comprehensive diagnostic panel |

| Medium (Level 2) | Known farms, uncertified | 21-30 days | Basic health screening |

| Low (Level 3) | Certified-clean partner herds | 14-21 days | Visual observation only |

For farmers buying from auctions, where the health history of animals is often a complete unknown, a High-Risk (Level 1) protocol is the only responsible choice. This means a longer duration and more extensive testing to uncover any hidden threats.

Test-and-Wait or Treat-All: Which Quarantine Strategy is Safer?

Once animals are securely in the quarantine zone, the next critical decision is how to clear them. Do you test for specific diseases and wait for results, or do you apply blanket treatments for common parasites and bacteria? The safest and most professional approach is not one or the other, but a strategic combination of both. A “Treat-All” strategy for common, treatable issues like internal and external parasites is a given. This should be done while animals are still in quarantine to prevent introducing resistant parasites to your main herd. However, this does not address the far greater threat of viral diseases.

This is where a “Test-and-Wait” strategy becomes non-negotiable. Relying on blanket treatments for viruses is impossible; you must identify what you’re dealing with. The cost of diagnostic tests can seem high, but it pales in comparison to the economic devastation of an outbreak. As veterinary research indicates that BVD is currently one of the costliest diseases of cattle, the investment in testing is a sound financial decision. The choice of which tests to run should be made in consultation with your veterinarian and based on several key factors.

Your Action Plan: Deciding Your Quarantine Testing Strategy

- Assess regional disease prevalence: Know what diseases are common in your area and the areas your new stock comes from.

- Calculate costs: Compare the cost of comprehensive diagnostic panels against the potential losses from an outbreak and the cost of blanket medication.

- Evaluate animal value: High-value genetic stock justifies a more extensive and expensive testing panel than commercial stock.

- Vaccinate and treat in quarantine: Align new animals with your herd’s vaccination schedule and treat for parasites before they are released.

- Consider source history: If available, use the source farm’s health certification status to guide your level of suspicion and testing intensity.

Ultimately, a “Test-and-Wait” approach for viruses is the only way to operate with certainty. It transforms your quarantine from a passive waiting game into an active, evidence-based investigation, which is the cornerstone of true biosecurity.

The Trailer Sharing Habit That Transmits Foot-and-Mouth Disease

The biosecurity fortress can have the strongest walls, but it’s worthless if you leave the gate open. In livestock operations, shared equipment is one of the most common “open gates,” and nothing is more dangerous than a shared or improperly cleaned transport trailer. Producers often focus on the animals themselves, forgetting that the environment they travel in is a perfect vector for disease. Habits like borrowing a neighbor’s trailer or using a third-party hauler without a verified cleaning history are gambles with catastrophic odds.

Diseases like Foot-and-Mouth Disease (FMD) are notoriously resilient. An infected animal can shed the virus in saliva, feces, and other bodily fluids, contaminating every surface of a trailer. The virus doesn’t simply die when the animal is unloaded. On the contrary, microbiological studies confirm that the FMD virus can persist in transport vehicles or animal housing for extended periods, waiting for the next susceptible animal. A trailer that carried an infected but asymptomatic animal in the morning can easily infect a healthy herd in the afternoon.

The only acceptable protocol is to assume every trailer is contaminated until proven clean. This means having a strict cleaning and disinfection (C&D) procedure for any vehicle that comes onto your property to drop off animals. The C&D process should involve removing all organic matter (manure, bedding) followed by the application of a broad-spectrum disinfectant known to be effective against resilient viruses like FMD. Ideally, you should use your own trailers for transport. If you must use a third-party hauler, you must demand proof of a recent, thorough C&D or, better yet, supervise the process yourself before your animals are loaded.

Treating a transport trailer with the same level of suspicion as a new animal is not paranoia; it is a fundamental and necessary step in preventing the introduction of a devastating epizootic disease.

How to Manage Visitor Access to Protect High-Health Herds?

Animals and equipment are not the only vectors of disease; humans are one of the most unpredictable and difficult to control. Every visitor to your farm—be it a veterinarian, a salesperson, a neighbor, or a delivery driver—is a potential carrier of pathogens on their boots, clothing, and vehicles. A high-health herd is an isolated fortress, and you are the gatekeeper. Managing visitor access with a strict, non-negotiable protocol is essential to maintaining that status.

The first principle is to eliminate all non-essential traffic. Access to the farm should be tightly controlled, ideally with a single, designated entry point. All other gates should be locked. Unauthorized vehicle entry must be prohibited; visitors should park in a designated area away from animal housing. For those whose visit is essential, a systematic screening process must be in place. The University of Illinois Veterinary Medicine department provides a clear and effective protocol for this.

Do not allow visitors who have traveled to countries with a history of foreign animal diseases such as foot-and-mouth disease. Do not allow international visitors for at least five days after arrival in the United States.

– University of Illinois Veterinary Medicine, Beef Cattle Biosecurity Module

This strict stance on international travel highlights the seriousness of the threat. Beyond this, a domestic visitor protocol is just as important. Every single visitor, without exception, should sign a logbook, detailing their name, company, and, most importantly, any recent contact with other livestock. Anyone who has been on another farm within the last 48-72 hours should be viewed as a high risk. Finally, personal protective equipment (PPE) is not optional. You must provide clean boots and coveralls or disposable alternatives for every visitor before they enter any animal area. Your farm’s biosecurity is your responsibility, not theirs.

Implementing a strict visitor policy may feel awkward, but it is a sign of professionalism. It demonstrates to your veterinarian and other professionals that you take the health of your herd seriously, and it protects your investment from a threat that can walk in on a pair of dirty boots.

How to Design a Chemical Storage Shed That Meets All Codes?

An effective quarantine protocol is not just defensive; it requires an offensive arsenal. Your ability to neutralize pathogens on equipment, in facilities, and on personnel depends on having the right chemicals stored correctly and ready for immediate deployment. This section isn’t about building a shed, but about stocking your biosecurity “armory.” This starts with a dedicated and organized “Quarantine Go-Box” and extends to a well-managed inventory of disinfectants. You must be prepared for a fight, and that means having your weapons ready.

The Quarantine Go-Box is an all-in-one kit containing everything needed to manage animals in the isolation unit without cross-contaminating the rest of the farm. It should be clearly labeled and used *only* in the quarantine zone. Its contents should include dedicated PPE (coveralls, boots, gloves), diagnostic sampling kits for your veterinarian, a small stock of emergency veterinary drugs as directed by your vet, and appropriate disinfectants. Having written protocols for monitoring animals and criteria for treatment (e.g., fever thresholds) within this box ensures consistent and correct procedures, even in a high-stress situation.

Choosing the right disinfectant is critical, as not all chemicals are effective against all pathogens. Your chemical inventory must include products proven to work against the specific viral and bacterial threats in your region. This means understanding the difference between classes of disinfectants and their proper use.

| Disinfectant Type | Effectiveness | Storage Requirements | Contact Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidizing agents (bleach) | High against enveloped viruses | Cool, dark storage | 10-30 minutes |

| Aldehydes | Broad spectrum | Ventilated area | 10-20 minutes |

| Quaternary ammonium | Moderate | Room temperature | 10 minutes |

Consult with your veterinarian to select the most appropriate disinfectants for your operation and ensure they are stored according to safety regulations and manufacturer instructions. An expired or improperly stored disinfectant is as useless as having none at all.

Group Housing or Stalls: Which Improves Sow Longevity?

While the specifics of housing design, like group housing versus stalls for sows, have their own complex considerations, they all operate under a single, overarching principle of biosecurity: separation. The most fundamental rule of quarantine is the creation of an unbreachable gap between the new, unproven animals and your established, high-health herd. This principle is absolute and non-negotiable, regardless of the species or housing system.

The concept is simple but must be enforced with paranoid diligence. It goes beyond just having animals in a different pen. True quarantine requires eliminating every possible avenue of direct and indirect contact. As experts from The Western Producer emphasize, this means no shared resources and no chance for physical interaction.

In livestock settings, quarantine means no shared fence lines and avoiding nose-to-nose contact. The quarantined animals should have separate equipment used only for their care.

– The Western Producer, Quarantine: traditional disease control

This “no shared fence lines” rule is critical. A standard fence is not a biosecurity barrier; it is a meeting point. It allows for nose-to-nose contact, aerosol transmission of pathogens, and the transfer of bodily fluids. A proper quarantine setup requires a “double-fencing” system, creating a corridor or “no-man’s-land” between the quarantine zone and any other animal area. This physical space acts as a buffer, making direct transmission impossible.

Furthermore, the directive for “separate equipment” must be taken literally. This means dedicated shovels, wheelbarrows, feed scoops, buckets, and needles. If a tool enters the quarantine zone, it stays in the quarantine zone or undergoes a full cleaning and disinfection protocol before being used anywhere else. The easiest way to enforce this is with a color-coding system—for example, all equipment with red tape is for quarantine use only. This simple visual cue removes ambiguity and reduces the risk of human error.

Ignoring this foundational principle renders all other efforts—testing, vaccination, visitor protocols—ultimately useless. A single lapse in separation can nullify weeks of careful quarantine.

Key Takeaways

- Assume Guilt: Every new animal is a potential “Trojan Horse.” Operate on the principle of “guilty until proven innocent” through rigorous testing.

- The Fortress Concept: Biosecurity is a multi-layered system. It includes physical separation, dedicated equipment, strict visitor protocols, and a ready chemical arsenal. A failure in one layer compromises the entire system.

- Vigilance is Not Optional: A biosecurity protocol is not a one-time setup. It requires constant review, auditing, and training to remain effective against evolving threats.

Why Monthly Veterinary Audits Save Money on Emergency Calls?

A biosecurity protocol is not a document that sits in a filing cabinet; it is a living system that requires constant vigilance, testing, and refinement. The greatest threat to a well-designed quarantine system is complacency. Over time, procedures can get sloppy, staff can forget key steps, and the sense of urgency can fade. This is why regular, scheduled audits conducted with your herd veterinarian are not a cost—they are an investment that prevents catastrophic expense down the line.

An emergency call for a widespread outbreak is a nightmare scenario. It involves massive treatment costs, production losses, potential culling, and long-term damage to your operation’s reputation and profitability. The cost of a monthly or quarterly veterinary audit is a tiny fraction of this potential loss. The devastating 2001 UK foot-and-mouth outbreak demonstrated that more than six million sheep and cattle were killed in the effort to control the disease. This is the price of reactive disease management. A proactive audit is designed to find the small cracks in your fortress before they become gaping holes.

The audit provides a fresh, expert set of eyes to review every aspect of your protocol. It’s an opportunity to walk through the process, check the integrity of facilities, review test results, update protocols based on new regional threats, and retrain staff. It keeps biosecurity at the front of everyone’s mind and reinforces its importance.

Your Checklist for a Monthly Quarantine Protocol Audit

- Review the plan: Go over your written quarantine protocols. Are they still relevant and practical? Early recognition of issues is crucial.

- Inspect physical barriers: Walk the quarantine facility. Check fences, gates, and drainage. Audit the cleanliness and state of repair.

- Analyze test results: Review all diagnostic results from the previous month’s arrivals with your veterinarian to identify any patterns or concerns.

- Update protocols: Discuss recent regional disease alerts with your vet and update your testing and vaccination strategies accordingly.

- Verify staff training and supplies: Confirm that staff are clear on all procedures and that the inventory of quarantine supplies and medications is complete.

Stop waiting for disaster to strike. Schedule a recurring biosecurity audit with your veterinarian today. Treating prevention as a core business function is the only way to protect your herd and your livelihood from the ever-present threat of epizootic disease.